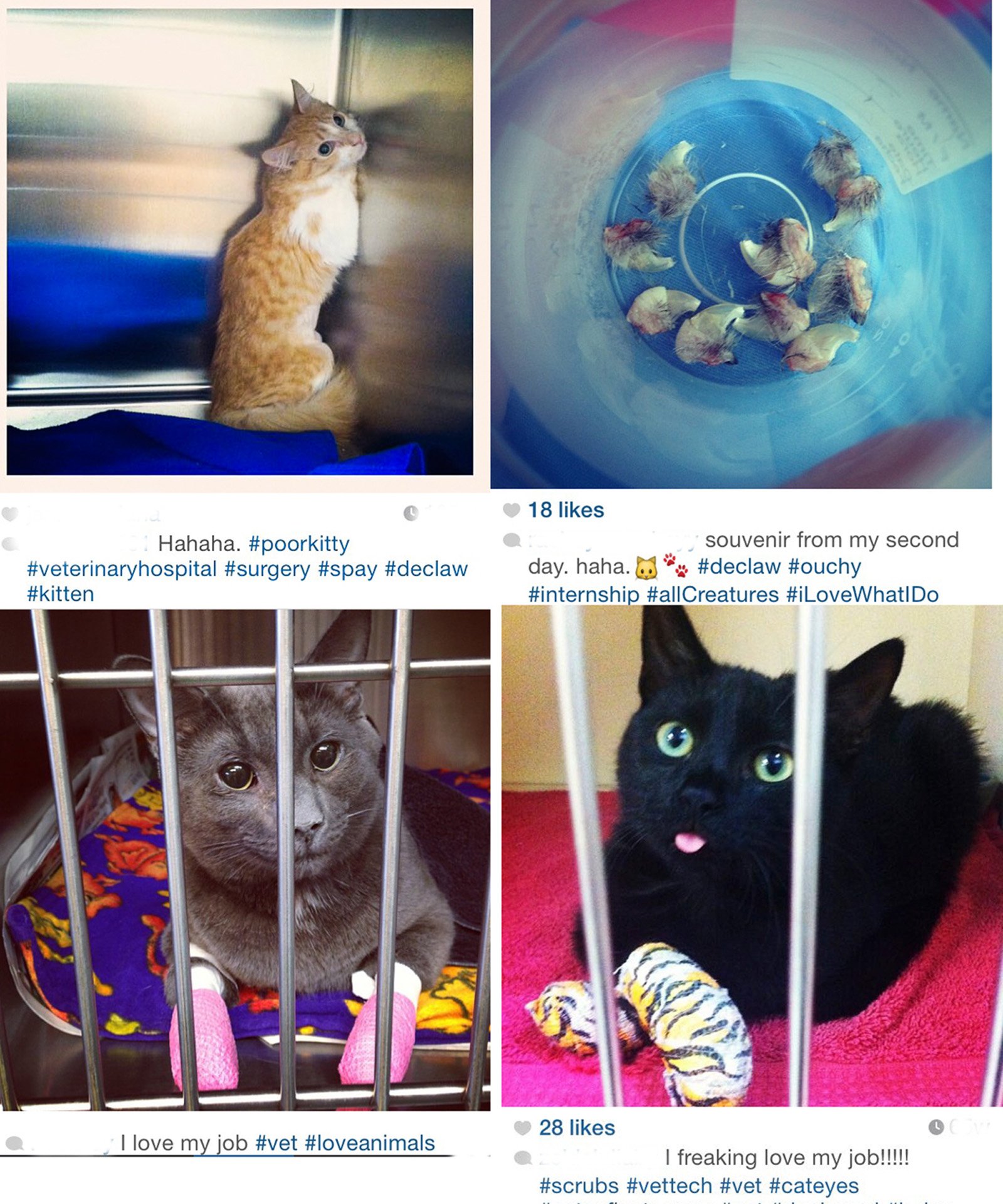

Here is a MAJOR study just published in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (JAVMA) You can read the whole thing but basically, in a nutshell, it shows that most veterinarians see debarking and earcropping as unnecessary procedures in veterinary medicine and NOW, finally, this study says that declawing should be looked at in the same way! It also says that there is clear evidence of pain

Here is a MAJOR study just published in the Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association (JAVMA) You can read the whole thing but basically, in a nutshell, it shows that most veterinarians see debarking and earcropping as unnecessary procedures in veterinary medicine and NOW, finally, this study says that declawing should be looked at in the same way! It also says that there is clear evidence of pain

and postoperative complications with declawing.

Hopefully, this will wake up the pro-declaw veterinarians who are performing this inhumane, cruel, and very unnecessary procedure and they will start taking the time to counsel their clients on how bad declawing is for their kitties and how to put in practice the humane alternatives such as scratchers and simple deterrents if there are scratching issues.

162 JAVMA • Vol 248 • No. 2 • January 15, 2016

In ancient Rome, during the First Century CE, Lucius

Columella wrote that it was proper to remove the

tails of puppies to prevent their growth to an “abominable

length” and to prevent madness, which is presumed

to refer to rabies.1 Although the idea that this

procedure could protect dogs against rabies has long

since been abandoned, tail docking is still commonly

performed, both because of a belief that it reduces

the incidence of injuries and because of the resulting

perceived improvements in aesthetics. However,

the effectiveness of this procedure in preventing injuries

has been questioned, and the idea of performing

this and other surgical procedures on animals solely

for cosmetic reasons has been heavily criticized in

many parts of the world.2 In fact, some countries have

passed legislation restricting these types of surgeries.

While anecdotal reports suggest that certain cosmetic

procedures such as ear cropping are in decline in

North America, to our knowledge there are no reliable

estimates on the numbers of these procedures performed

annually.

Most surgical procedures performed on dogs and

cats in North America are performed for therapeutic,

diagnostic, or preventive purposes; that is, they are

medically necessary. In contrast, procedures that are

not necessary for maintaining health or that are not

beneficial to the animal can be classified as MUSs. This

would include procedures performed mainly to alter

the appearance of animals (eg, ear cropping and tail

docking in dogs), procedures performed solely to prevent

behaviors that are destructive or annoying (eg,

devocalization and defanging in dogs and onychectomy

in cats), and procedures of dubious or minimal

benefit (eg, dewclaw removal in dogs). Note that elective

neutering of healthy dogs and cats has historically

been performed to prevent or reduce the risk of future

health problems (eg, pyometra, mammary gland

neoplasia, and reproductive tract–related neoplasia)

and to prevent unplanned breeding, which benefits

the population as a whole by reducing the number

of unwanted animals.3 Thus, for the purposes of the

A review of medically unnecessary surgeries

in dogs and cats

Katelyn E. Mills BSC

Marina A. G. von Keyserlingk PhD

Lee Niel PhD

From the Animal Welfare Program, Faculty of Land and Food Systems, University of

British Columbia, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z6, Canada (Mills, von Keyserlingk); and the

Department of Population Medicine, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph,

Guelph, ON N1G 2W1, Canada (Niel).

Address correspondence to Dr. Niel (lee.niel@uoguelph.ca).

present review, we did not classify elective neutering

of dogs and cats as an MUS, even though there is

evidence that elective neutering, while decreasing the

risk of certain health issues in dogs, may increase the

risk of others.4

MUSs Commonly Performed

on Dogs and Cats

Tail docking

Tail docking (caudectomy) is the surgical removal

of the distal portion of the tail. In the Middle Ages, tail

docking was performed on hunting and fighting dogs

to lessen the risk of injury to the tail5 and is still commonly

performed on dogs of various hunting, working,

and terrier breeds. Tail docking is most often done

within the first week after birth. Typically, a scissors

or scalpel is used to remove the distal portion of the

tail, with 1 or more sutures used to close the resulting

wound. Alternatively, an elasticized band is placed

around the tail, causing loss of tissue circulation and

eventual death and sloughing of the tail.6 According to

1 study,6 tail docking is often carried out by dog breeders

without the use of anesthetics or analgesics. Even

when tail docking is performed by veterinarians, anesthetics

or analgesics may not be used, with 1 study6

finding that only 10% of veterinarians used anesthetics

or analgesics in conjunction with tail docking. Given

that the use of anesthetics and analgesics in veterinary

practice has increased in general since that study was

published,7 it is possible that the percentage of veterinarians

using pain management techniques in conjunction

with tail docking has also increased. However,

good estimates are not available.

Tail docking is sometimes performed in adult dogs

because of tail injury, neoplasia, or self-trauma and in

these instances would be considered a medically necessary

surgery. Note that treatments other than tail

docking have been described for dogs with self-trauma

of the tail, including behavioral modification and

pharmacologic treatment.8 However, the efficacy of

these alternative treatments has not been examined.

One argument in favor of tail docking is that these

breeds require docking to avoid future tail injury.2 To

ABBREVIATIONS

CVMA Canadian Veterinary Medical Association

MUS Medically unnecessary surgery

Reference Point

JAVMA • Vol 248 • No. 2 • January 15, 2016 163

test this theory, Diesel et al9 completed a case-control

study of tail injuries in working and nonworking

dogs with and without docked tails. Tail injuries that

were reported included fractures, dislocations, lacerations,

contusions, self-trauma, and neoplasia. The

weighted risk of tail injuries in working dogs (0.29%)

was significantly higher than the risk in nonworking

dogs (0.19%), and the risk for dogs with docked tails

(0.03%) was significantly lower than the risk for dogs

without docked tails (0.23%). However, the overall tail

injury rate was quite low, and the authors estimated

that 500 dogs would need to have their tails docked

to prevent 1 tail injury.9 A separate study10 reported

similar results, with a tail injury risk of 0.90% for working

breeds and 0.53% for nonworking breeds, and an

estimate that 232 dogs would need to have their tails

docked to prevent 1 tail injury severe enough to require

treatment by a veterinarian. Recently, Lederer et

al11 examined owner reports of tail injuries in docked

and undocked hunting dogs during the shooting season

in Scotland and found that rates of injuries were

higher in undocked spaniels and undocked dogs of

the hunt, point, and retrieve breeds. The authors also

found that the number of injuries reported for both

docked and undocked hunting dogs was higher than

previously reported for working and nonworking

dogs. For example, 54.7% of undocked spaniels and

20.8% of docked spaniels reportedly had at least 1 injury

during the shooting season. However, only 4.4% of

dogs with a tail injury required veterinary treatment,

suggesting that the risk of serious injury was much

lower than the overall injury estimate. These results

indicate that there may be some minor benefits to tail

docking but likely only in particular breeds of dogs

that are participating in hunting activities.

Notably, a number of dog breeds, including the

Pembroke Welsh Corgi and Australian Shepherd, have

a naturally occurring mutation in the T-box transcription

factor T gene (C189G) that results in a short-tail

phenotype.12 In addition, a few breeds with naturally

occurring short tails do not have this mutation, suggesting

that there are other yet-to-be-discovered genetic

factors affecting tail phenotype. Recently, selective

breeding by outcrossing to a Pembroke Welsh Corgi

with the natural bobtail gene resulted in the birth of

Boxers with naturally short tails.13 Thus, it may be possible

for breeds that traditionally have undergone tail

docking to develop family lines with naturally short

tails. Note, however, that there have been anecdotal

reports that breeding for a bobtail appearance has resulted

in health concerns related to deformed tails and

spinal cord defects. Unfortunately, no scientific literature

is available on this topic, and the extent of this

problem is currently unknown.

Individuals disagree as to whether there is pain

associated with tail docking. When asked about the

degree of pain associated with tail docking in puppies,

82% of dog breeders sampled in Australia indicated

“none” or “mild.”6 In contrast, the majority of

veterinarians (76%) reported the associated pain to

be “significant” or “severe.” In a study14 of 50 puppies

(Doberman Pinschers, Rottweilers, and Bouviers des

Flandres) that underwent tail docking at 3 to 5 days of

age, all puppies vocalized intensely at the time of tail

amputation, indicating that the procedure was indeed

painful. The authors also reported that the puppies

settled down relatively quickly after the procedure,

suggesting that the pain did not last long; however,

puppies were only monitored until they settled, which

took approximately 3 minutes, and further pain behaviors

may have occurred at later time points. Despite

the seemingly short duration of pain, some opponents

of tail docking have argued that any pain is unjust if it

is unnecessary.15

Whether tail docking can result in chronic pain

in dogs has not been extensively studied. Gross and

Carr16 described 5 Cocker Spaniels and a Miniature

Poodle that had extensive self-trauma at the surgical

site for several months up to 1 year after tail amputation

and reported that application of mild pressure to

the affected tail areas elicited a severe pain response.

The pain in these dogs was attributed to neuroma development.

Young female cattle that have undergone

tail docking show increased agitation following application

of hot or cold packs to the tail stub, suggesting

that hypersensitive nerve bundles may be present,17

and up to 80% of human amputees report experiencing

phantom pain following limb amputation.18 Thus,

there is a potential for neuropathic pain in dogs following

tail docking, although whether or how frequently

this occurs is unknown.

Tail docking may also have detrimental effects on

social communication in dogs,19 as research suggests

that social communication in dogs is largely reliant on

body language, with the tail playing an important role.

For example, Leaver and Reimchen19 examined behavioral

responses to dogs with different tail lengths by

placing a remotely controlled life-sized dog replica in

a park. They assessed responses to tails that were short

or long and to tails that were wagging or still. Large

dogs showed more caution approaching the replica

dog when it had a short tail than when it had a long

tail, and the authors speculated that this was a consequence

of failure by the replica dog to signal. Also,

large dogs approached the replica dog with a long, still

tail less frequently than they approached the replica

dog with a long, wagging tail but approached replica

dogs with short, wagging tails and short, still tails

with about equal frequency. In contrast, small dogs

showed greater caution than large dogs, regardless of

tail length or motion, likely because of the height difference

and the small dogs’ inability to view the tail.

Results of this study indicated that social communication

in dogs relies on proper observation of tail signaling,

suggesting that tail docking may impair social

communication in dogs.

Collectively, the available evidence suggests that

tail docking is unnecessary as a routine procedure to

prevent injury, particularly in nonworking companion

dogs; that it causes short-term pain and has the po164

JAVMA • Vol 248 • No. 2 • January 15, 2016

tential to cause long-term neuropathic pain in some

animals; and that it impairs social communication,

which could lead to increased negative interactions

with other dogs.

Ear cropping

In dogs, ear cropping involves reshaping the appearance

of the external ear, usually by removing up

to half of the caudal portion of the pinna (auricula).

Following removal of the pinna, the ears are taped and

splinted to facilitate healing in the desired shape. This

procedure is typically performed when puppies are

between 9 and 12 weeks old, after they have received

their initial vaccinations.20 Most often, dogs are anesthetized

during the procedure and may or may not be

given analgesics afterward.

Historically, ear cropping was performed to prevent

ear damage during hunting or fighting, and some

proponents of ear cropping continue to suggest that

cropping is necessary to prevent accidental tearing

of pendulous ears, particularly in hunting dogs. However,

there is no evidence to support these claims, and

many working breeds, such as spaniels and retrievers,

have naturally pendulous ears. It has also been suggested

that ear cropping reduces the risk of ear infection,

as a result of less trapping of moisture and debris

in the ear canal.21 While there is some evidence to suggest

that dogs with pendulous ears have a higher risk

of otitis externa, compared with dogs with erect ears,

it appears that specific breeds tend to have a higher

predisposition than others regardless of ear conformation.

22,23 For example, 1 study found that otitis externa

is more common in Cocker Spaniels, Poodles, and German

Shepherd Dogs,24 and another found a higher

prevalence in Golden Retrievers and West Highland

White Terriers.23 None of these breeds traditionally

have their ears cropped, and their natural ear position

varies between hanging and erect. At least 1 textbook

on veterinary surgery25 no longer includes detailed information

on ear cropping in dogs because of ethical

concerns associated with the procedure, with the authors

indicating their support for the AVMA position

statement against this procedure.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no published

studies on whether ear cropping results in

acute or chronic pain in dogs, although given the

length of the resulting wound, it is clear that the procedure

results in some level of acute pain. However,

information is lacking on common anesthetic and analgesic

practices for dogs undergoing ear cropping. In

addition, we are not aware of any studies on whether

alterations in ear conformation influence communication

with humans or other dogs.

Importantly, ear cropping is no longer taught at

colleges of veterinary medicine in the United States.

Thus, veterinarians performing this procedure in the

future will largely be self-taught,26 particularly as veterinarians

experienced with this procedure retire.

Some veterinarians have justified performing this

procedure because of concerns that serious complications

and animal welfare issues will arise if the procedure

is done by unqualified individuals who are not

veterinarians and do not have access to appropriate

facilities, anesthetics, and analgesics.26

Dewclaw removal

In dogs, the dewclaws represent the vestigial first

digits of the forelimbs and, occasionally, hind limbs.27

Some breeds, such as the Great Pyrenees, Bauceron,

and Norwegian Lundehund, have double dewclaws on

each of the hind limbs.28 Dewclaw removal is typically

performed within the first few days after birth, usually

without anesthesia or analgesia,29 but it may also be

performed later in life (eg, when the dog is spayed or

neutered).30 Sedation and local anesthesia are recommended

when performing this procedure on young

puppies, and general anesthesia is recommended for

older animals.31

The main argument in support of dewclaw removal

is that it prevents injuries associated with accidental

tearing of the dewclaws.29 While the forelimb

dewclaws are typically attached by bone, the hind

limb dewclaws are often attached only by skin, which,

some have suggested, makes them prone to catching

and tearing. Furthermore, because there is no wear of

the associated nail, regular trimming is required to reduce

the chances of the nail being caught. However, to

date, no research is available to determine the actual

incidence of dewclaw tearing, so the true scope of this

problem is unknown.

To our knowledge, the impact of dewclaw removal

on the welfare of dogs has not been researched. As

with any surgery, there is the potential for acute and

chronic pain, but the severity of the pain is unknown.

Declawing

Declawing (onychectomy) is an elective surgical

procedure that involves removal of the claws

through amputation of all or part of the distal phalanx.

Several variations of the procedure have been

described, including removal of the entire distal phalanx

with a scalpel or surgical laser and removal of

all or most of the distal phalanx with a nail clipper.32

Removal of the distal phalanx with a surgical laser

appears to be the quickest procedure and is associated

with lower levels of postoperative stress and pain

than removal with a scalpel.33 However, it has also

been associated with a higher number of postoperative

complications in the days following the procedure.

33 Transection of the tendons of the deep flexor

muscle (ie, tendonectomy) is sometimes performed

as an alternative to onychectomy, as it prevents extension

of the claws and results in fewer signs of

pain.34 Both onychectomy and tendonectomy should

be performed only by veterinarians with appropriate

anesthesia and postoperative analgesia.

Declawing is usually performed to prevent

scratching-related injuries to people and damage to

property. Recent surveys35,36 of veterinarians indicate

that aggression and property destruction due to

JAVMA • Vol 248 • No. 2 • January 15, 2016 165

scratching are frequent behavior problems reported

by cat owners. Scratching of people and other animals

is undesirable because of the potential for injury and

infection, particularly in people who are immunocompromised.

In some cases, this scratching may be

intentional and related to aggression, but in others it

is unintentional during play and handling. There appears

to be a relatively high prevalence of aggression

in owned cats, with recent research suggesting 36%

of cats display aggression toward their owners37 and

almost 50% of cats display aggression toward either

familiar or unfamiliar people.38 However, although declawing

will prevent scratching-related injuries, it is

unlikely to resolve the problem of aggression in general

owing to the potential for cats to bite as an alternative

to scratching. More research is needed to identify

means to prevent aggression-related behaviors by cats

toward their owners.

Scratching items in the environment is a normal

behavior that serves a number of functions for cats,

including territorial marking and nail conditioning.39

Farm cats have been reported to scratch between 1

and 6 times a day. Scratching behavior is driven almost

entirely by the presence of conspecifics39 but is still

present in cats housed singly in homes. Although it is a

normal behavior, environmental scratching is generally

deemed to be undesirable by owners because it can

lead to property damage. While recent estimates of the

prevalence of environmental scratching are unavailable,

2 older studies40,41 suggest that 15% to 25% of

cats show inappropriate scratching of property, with

one of these studies40 indicating that scratching might

increase the risk of cat relinquishment. Although declawing

is 1 method of preventing scratching damage,

there are alternative methods that do not involve

surgery. For example, owners can provide appropriate

outlets for scratching and trim their cats’ nails regularly.

Therefore, when this procedure is requested, every

effort should be made to educate and assist owners of

cats to pursue possible alternatives that could alleviate

the need for surgery.

The National Council for Pet Population has estimated

that approximately 14.4 million of the 59 million

cats in the United States are declawed.42 Similarly,

a recent study43 reported that 20% of cats admitted

in the Raleigh, NC, area had undergone declawing

or, more specifically, onychectomy. Interestingly, the

percentage of cats that are declawed has apparently

not changed in the past decade despite the growing

controversy surrounding the procedure.43 In a survey

conducted by Yeon et al,34 cats reportedly continued

to make scratching movements following declawing,

but 91% of owners surveyed had an overall positive

attitude about the procedure, whether onychectomy

or tendonectomy.

Various studies44–47 have demonstrated that onychectomy

causes postoperative pain in cats. For example,

Carroll et al44 examined postoperative pain in cats

receiving either butorphanol or no analgesia following

onychectomy and found that in comparison to control

cats, butorphanol-treated cats had higher analgesia

scores during the first 24 hours after surgery. Furthermore,

according to owner reports, butorphanol-treated

cats were more likely to eat and act normally and to

have lower lameness scores during the first day after

discharge. Cloutier et al45 found that even when cats

were treated with butorphanol before surgery, they

had evidence of postoperative pain, as determined by

comparison with control cats that underwent a sham

procedure. Both of these studies involved removal of

the distal phalanx with a scalpel or clipper, but recent

studies assessing the effect of laser removal suggest

that this procedure also results in postoperative pain,

although to a lesser degree than that associated with

other methods. Clark et al46 found that cats that underwent

laser onychectomy were less reluctant to jump

after surgery than were cats in which onychectomy

was performed with a scalpel or clipper. Similarly,

Holmberg and Brisson47 compared pain scores during

the 10 days following onychectomy with either

a scalpel or a laser and found that both groups had

elevated pain scores during the first 9 days but that

the mean score over the first 7 days was higher for the

scalpel group, compared with the laser group. Finally,

Robinson et al33 assessed limb function by measuring

ground reaction forces following laser or scalpel

onychectomy and found that forces were reduced in

both groups following surgery, but the reduction was

greater in the scalpel group.

Researchers have also studied the pain associated

with tendonectomy versus onychectomy, but differences

between the procedures are unclear. While

1 study48 found that tendonectomy resulted in lower

pain scores, compared with onychectomy, during the

first 24 hours after surgery, another study45 found no

differences in pain scores when comparing the 2 procedures.

Jankowski et al48 reported differences in postoperative

complications associated with the 2 procedures.

Of 18 cats that underwent onychectomy, 1 had

severe postoperative pain and another had long-term

lameness. Of 20 cats that underwent tendonectomy,

1 had long-term lameness, but owners of 6 cats expressed

dissatisfaction with the procedure because of

continued scratching and issues with claw growth and

trimming.

Although both onychectomy and tendonectomy

have the potential to cause acute postoperative pain,

it is likely that a multimodal analgesic approach will

provide adequate pain control. Although a review of

all studies assessing efficacy of analgesic regimens for

control of postoperative pain following onychectomy

and tendonectomy is beyond the scope of the current

discussion, we encourage future research to determine

which analgesic regimes are commonly used

in current veterinary practice and whether they are

sufficient.

A number of studies have assessed short-term

and long-term postoperative complication rates following

onychectomy. Short-term postoperative complications

following onychectomy include pain and

166 JAVMA • Vol 248 • No. 2 • January 15, 2016

associated lameness, hemorrhage, swelling, infection,

and changes in behavior.48,49 Pollari and Bonnett50

examined the risk of postoperative complications

when onychectomy was performed alone or in combination

with other surgeries and reported that cats

that underwent onychectomy in combination with

ovariohysterectomy or castration were more likely

to have postoperative complications than were cats

that underwent either procedure alone. This was particularly

concerning because 53% of cats underwent

both procedures.

One common long-term complication of onychectomy

is claw regrowth, with rates reportedly

ranging from 3.4% to 15.4%, depending on the study

and the method of claw removal.46,48,49 One study46

found that claw regrowth was more common with use

of a nail clipper than with use of a scalpel or laser

(15.4% vs 6.5% and 3.4%). Other long-term complications

include persistent lameness and signs of chronic

pain.46,48,49 Clark et al46 reported the highest rates of

pain-related complications, with up to 23% of cats

having ongoing lameness and 42.3% of cats showing

signs of pain on paw palpation. Owners have also reported

long-term behavioral changes in cats following

onychectomy such as house soiling and an increased

resistance to allowing the paws to be handled or an increased

incidence or severity of biting, compared with

behavior before the procedure.51

Alternatives to declawing include regular nail

trimming and use of artificial nail caps to minimize

property damage and provision of appropriate

scratching surfaces such as scratching posts and substrates.

52 A study53 of 128 Italian cat owners found that

sexually intact male cats were more likely to scratch

other surfaces when a scratching post was absent

from the environment, and Cozzi et al39 reported that

a feline interdigital semiochemical, a cat pheromone

replacement made of fatty acids, can be used to control

excess behavioral scratching through placement

of this substance on a desired scratching location.

Behavior modification methods may also decrease environmental

scratching. Given clear evidence of pain

and postoperative complications with declawing, this

procedure should be considered as a last resort after

all other behavior modifying measures have been attempted

and when the only other alternative is relinquishment

or euthanasia.

Devocalization

In dogs, devocalization (ventriculocordectomy)

involves complete or partial removal of the vocal folds

to prevent vocalization or reduce the intensity of vocalizations

that are produced. The procedure can be

done through an oral approach or by means of a laryngotomy.

Anecdotally, the oral approach appears to

be more commonly used in clinical practice, although

laryngotomy is the recommended approach.54 Devocalization

procedures vary in effectiveness, with great

variation among breeds.54 In particularly excitable

dogs, increased airflow through the larynx following

devocalization can result in the ability to bark to some

degree.54 As a result, some owners administer tranquilizers

after surgery.54

Excessive barking is seen as an undesirable behavior

by owners and others affected by the barking and

reportedly increases the risk of relinquishment.55,56

One study56 found that excessive barking accounts

for 11.3% of reported undesirable behaviors in dogs.

Alternatives to devocalization are typically aimed at

addressing the underlying cause of the undesirable

barking. Common causes of undersirable barking include

general anxiety, separation anxiety, and compulsive

disorders,57 and treatment by means of behavior

modification with or without adjunctive medication

should be attempted first. One study58 found that

positive reinforcement training was effective at reducing

barking in response to someone knocking at the

door, and dogs that are exercised more frequently are

found to bark less than dogs that are not exercised.59

While there appears to be general agreement within

the veterinary behavior community that positive reinforcement

is the most appropriate training method

for dogs, barking is often treated through the use of

methods that incorporate positive punishment. Both

electric shock and citronella spray collars have been

found to reduce the incidence of certain types of barking.

60,61 However, the effectiveness of citronella spray

collars is decreased when the collar is worn continuously,

and a rebound effect (increased barking) is

frequently observed after the collar is removed.60 In

addition, there are concerns that electric shock and

citronella spray collars may cause fear and pain in

dogs. One study61 found no difference in serum cortisol

concentrations between dogs wearing electric

shock or citronella spray collars and control dogs.

However, another study62 found behavioral signs of

fear and stress in dogs in response to use of an electric

shock collar, including lowered posture, vocalizations,

oral behaviors, and aggression toward the handler.62

In addition, when used improperly, electric shock collars

can lead to burns and infections. Finally, in dogs

with excessive barking, devocalization only removes

the manifestation of the problem (ie, the dog is no

longer being able to bark) and does not address the

underlying behavioral problem, which may be negatively

affecting the dog’s quality of life. Thus, in dogs

with excessive barking, the underlying cause should

be identified and addressed before devocalization is

considered.

A potential long-term complication of devocalization

in dogs is formation of a laryngeal web that obstructs

airflow63 and may require corrective surgery.31

Laryngeal web formation occurs more commonly after

devocalization through an oral approach, with clinical

signs developing between 3 months and 3 years

after surgery in 1 report.63

Defanging

Defanging involves removal or reduction of the

canine teeth and can be performed in either puppies

or adult dogs. Although this procedure should only be

performed with appropriate dental techniques, it is,

JAVMA • Vol 248 • No. 2 • January 15, 2016 167

in some cases, performed by cutting or breaking the

teeth near the gingival margin and may or may not

involve adequate anesthesia and analgesia.64

Defanging was originally developed to decrease

the danger captive wild animals posed to humans,

and similar justifications have been presented by advocates

of this procedure in companion animals.65

Although aggression can be a serious concern in certain

dogs, this procedure is not fully effective at reducing

the risks of biting injuries. Appropriate treatment

of aggression should involve risk management and

treatment to reduce the behavior problem. Although

research has not been conducted on pain and behavioral

effects of defanging in companion animals, this

procedure is considered unnecessary when trying

to prevent human-animal conflicts with exotic carnivores

and similar results can be predicted for companion

animals.65

Legislation Related to MUSs

Some of the earliest legislation restricting MUSs

in dogs and cats was passed in the European Union

in 1987, when the European Convention for the Protection

of Pet Animals was implemented. This treaty

prohibits any “surgical operation for the purpose of

modifying [the] appearance of a pet animal or for

other non-curative purposes,”66 which would include

tail docking, ear cropping, devocalization, declawing,

and defanging. Veterinarians can make exceptions

to these prohibitions if the procedure is considered

necessary for curative reasons or the benefit of a particular

animal, or to prevent reproduction.66 However,

regardless of the reason, all surgical operations must

be carried out by a veterinarian and under anesthesia

if the animal is believed to be in, or have the possibility

of being in, severe pain.66 Although this convention

was initially ratified by 4 member states in 1992, it is

noteworthy that as of 2014 some members of the EU

had yet to ratify it. In some of the countries that have

not yet ratified the convention, alternative legislation

restricts at least some of these procedures. For example,

in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands, ear

cropping, tail docking, and declawing are restricted. In

addition, some countries, such as France, have ratified

the convention but excluded tail docking from the list

of prohibited procedures.67

Many additional countries have incorporated

MUSs into their animal welfare legislation, but recommendations

vary by country. For example, declawing,

ear cropping, and tail docking are restricted

in Australia and Israel; declawing, devocalization,

and ear cropping are restricted in New Zealand; and

tail docking and ear cropping are restricted in Brazil.

We are not aware of legislation in any countries

that restricts surgical removal of the dewclaws in

dogs.

Current Status in North America

Both the CVMA and AVMA have a number of position

statements regarding MUSs. For instance, the

AVMA position statement on tail docking and ear

cropping states that it “opposes ear cropping and tail

docking of dogs when done solely for cosmetic purposes.”

68 The AVMA has also produced comprehensive

literature reviews and fact sheets to support these

position statements. The CVMA has taken a stronger

stance by indicating that the organization “opposes

the alteration of any animal by surgical or other invasive

methods for cosmetic or competitive purposes,”

which includes tail docking and ear cropping in dogs

as well as cosmetic dentistry, tattooing, and piercing.69

Although these position statements are decidedly

against MUSs, they are ultimately only suggestions because

these organizations have no enforcement capabilities.

Indeed, veterinarians practicing in Canada

and the United States are still able to perform these

procedures at their own discretion, with a few exceptions.

In addition, anecdotal reports suggest that some

procedures, most notably tail docking, are performed

by breeders without the assistance of a veterinarian.

It has been suggested that some veterinarians elect to

continue tail docking puppies in fear that failure to do

so will result in less qualified people, such as breeders,

undertaking the procedure without access to proper

medical facilities and appropriate analgesics.2 This

concern is supported by a study6 that found 51% of

the breeders that were surveyed were performing the

procedure on their own.

The CVMA position statement on cosmetic alterations

also states that the association “strongly

encourage breed associations to change the breed

standards” in the hopes that the number of dogs

that are ear cropped and tail docked will decrease.69

Breed standards in Canada and the United States

have changed to allow showing of dogs that have not

undergone ear cropping or tail docking. This is likely

to have reduced the number of dogs undergoing

these procedures, but relevant figures are not available.

Although the Canadian Kennel Club and American

Kennel Club do not encourage these procedures,

they also do not specifically discourage them. The

American Kennel Club, for instance, states that it

endorses “acceptable practices integral to defining

and preserving breed character and enhancing good

health.”70

The CVMA and AVMA also have position statements

against MUSs used primarily for behavioral

modification, including declawing, devocalization, and

removal or reduction of the teeth.52,69,71,72 For example,

the CVMA position statement on onychectomy

of domestic cats states that the association “strongly

discourages onychectomy of domestic cats for routine

purposes” as it “prevents cats from expressing normal

behaviors and causes pain.”52 The AVMA position

statement echoes this message and encourages client

education and other preventive measures be taken before

declawing is considered. Similar suggestions for

attempts at behavioral modification to prevent the

problem behavior are included in the devocalization

position statements of both the CVMA and AVMA.

However, for each of these position statements there is

168 JAVMA • Vol 248 • No. 2 • January 15, 2016

little guidance as to what attempts at alternative strategies

are sufficient to justify the need for these procedures.

Thus, owners with a lower tolerance for behavioral

problems may elect to pursue them without

first attempting alternative strategies.42 Notably, pursuing

alternative strategies to correct behavior problems

related to scratching, aggression, and barking can

involve substantial time, expertise, and expense, and

owners may not be willing to invest their resources in

alternative strategies when a surgical option is available.

Some have argued that if these procedures were

unavailable, such owners might opt for relinquishment

or euthanasia. However, many veterinary clinics

offer declawing of kittens in conjunction with spaying

or neutering as a preventive measure when scratching

behavior is not yet a concern. Thus, further discussion

among stakeholders to determine how best to balance

these ethical tradeoffs with an aim toward reducing

the number of these procedures being performed is

needed.

The role of national veterinary organizations such

as the CVMA and AVMA in reducing the number of

MUSs that are performed should not be underestimated.

In some cases, their position statements have been

incorporated into regulations initiated by provincial

or state regulatory bodies to restrict veterinarians

from performing these surgeries. For instance, restrictions

on veterinarians performing ear cropping and,

in some cases, tail docking have been incorporated

into the bylaws of veterinary organizations in 6 Canadian

provinces (British Columbia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan,

Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick,

and Prince Edward Island).73 However, these restrictions

do not apply to nonveterinarians who may be

performing tail docking and dewclaw removal outside

of a clinic environment. Newfoundland and Labrador

is the only Canadian province that has incorporated

MUSs into formal legislation. In this province, the Animal

Health and Protection Act was passed in 2010,

banning ear cropping in dogs for the purposes of conforming

to breed standards.74 Additionally, this province

has bylaws that prohibit docking of tails in all

animals except when medically necessary.

A number of similar bylaws have been created in

some states within the United States, many of which

are based in principle on the AVMA guidelines. Fourteen

states restrict tail docking in some species; however,

only Maryland and Pennsylvania restrict tail

docking of dogs.75 In Pennsylvania, this restriction is

for unqualified persons performing the procedure after

5 days of age, but veterinarians can perform the

surgery regardless of age.75 Legislation restricting ear

cropping of dogs is the most common in the United

States, with 9 states having restrictions. In the case of

Washington State, ear cropping is permitted when in

line with good husbandry practices.75 After the CVMA

released a position statement in 2009 that “discourages

devocalization of dogs unless it is the only alternative

to euthanasia,” and the AVMA released a similar

statement 4 years later, a law was passed in Massachusetts

that banned this procedure.76 Devocalization is

also prohibited in 4 other US states, unless medically

necessary. In addition to state-level restrictions, municipalities

have in some cases implemented bylaws

restricting MUSs in animals. For example, declawing

is banned in a number of municipalities throughout

California.

While veterinary organizations in North America

have been clear about discouraging various MUSs

through the publication of position statements, their

role to date has been relatively passive. In contrast, the

Australian Veterinary Association actively called for a

ban on tail docking in dogs starting in 2008,77 which

was in part responsible for passage of national legislation

banning this procedure. This legislation ensures

that no persons in Australia, including nonveterinarians,

can perform this procedure. We would suggest

that there may be value in veterinarians in Canada and

the United States taking a similar stance in suggesting

formal legislation as a method of reducing the number

of MUSs in dogs and cats.

Public Attitudes Toward

MUSs in Dogs and Cats

Community consensus regarding right and wrong

governs the actions of society, which then forms

policies and laws.78 Challenges arise when there is

disagreement among stakeholders, preventing a consensus

from being reached. This is the case for many

MUSs, in that stakeholders differ in what they consider

to be acceptable. Given the distributed authority

governing companion animal welfare regulations and

legislation in Canada and the United States, it is not

surprising that leadership comes in large part from

the CVMA and AVMA, in combination with the Canadian

and American kennel clubs and specific breed

associations. Equally disconcerting is that despite the

American Kennel Club stating that unaltered dogs will

not be disqualified when entered into competitions,79

many owners believe that failure to comply with traditional

breed standards will reduce their dogs’ chances

of winning. Some organizations have argued that banning

these procedures is a violation of an individual’s

rights. For example, the United Kingdom–based Council

of Docked Breeds campaigns to protect the owner’s

right to choose tail docking as an option, arguing

that legislating these practices removes a person’s

freedom of choice.80

Social distance is defined as the emotional, psychological,

and physical distance between one individual

and another, typically 2 humans.81 In the past few decades,

the social distance between humans and companion

animals has decreased drastically. This likely

accounts for the change in attitudes regarding what is

acceptable versus unacceptable in relation to animal

treatment, with the effect that practices that were once

seen as being acceptable are now questioned.81 In

some cases, language choice can be used to influence

stakeholders and evoke emotion, a strategy commonly

used by animal rights advocates, who employ words

JAVMA • Vol 248 • No. 2 • January 15, 2016 169

such as oppression, suffering, and cruelty to appeal

to human emotion.82 In other cases, euphemisms can

be used to increase social distance and decrease empathy.

Both the CVMA and AVMA have acknowledged

these potential concerns in their position statements

regarding declawing and devocalization by stating that

owners must be educated with regards to the potential

alternatives, the details of the procedure to be performed,

and the potential risks. However, there are no

data available to determine how often these conversations

between veterinarians and owners occur or what

effect they have on the owner’s willingness to proceed

with the procedure. Further research in this area is

critical to accurately gauge current societal views on

MUSs in dogs and cats.

Conclusions

We strongly believe that in a clinical setting, surgical

procedures should be performed on animals only

if they have or can be expected to have clear benefits

for the animal or the population as a whole. At a minimum,

the procedures discussed in the present review

all cause some degree of acute pain and are associated

with some risk of infection or other adverse effects.

Society’s attitudes toward dogs and cats have changed

over time, likely because of decreased social distance,

with the result that attitudes toward certain procedures

that were once considered acceptable are now

being reconsidered. In many countries, discussions

among broad ranges of stakeholders have resulted in

legislation banning surgical procedures that are considered

elective or unnecessary.

People are willing to acknowledge that animals

experience pain but do not always appear to be willing

to take appropriate action to treat or prevent

that pain.83 This appears to be true in the case of the

procedures discussed in the present review, which

are known to be painful but are still commonly performed.

84 We recommend the following strategies

for enacting change in Canada and the United States

with regards to MUSs in dogs and cats. First, further

research and education are needed on effective methods

for preventing or treating the underlying behavior

problems that traditionally have resulted in declawing,

devocalization, and defanging. Second, further

research on public attitudes toward MUSs is needed;

specifically, understanding the beliefs and values held

by the public must be a priority, as only then will it be

possible to encourage policy and legislation that accurately

reflect the views of current society. Third, veterinarians

should take a leadership role in educating

both owners and the broader public on the important

topic of MUSs in dogs and cats.

References

1. Columella LJML. L Junius Moderatus Columella of husbandry.

In twelve books: and his book concerning trees. Translated

into English, with several illustrations from Pliny, Cato,

Varro, Palladius, and other ancient and modern authors.

London: A. Miller, 1745;335.

2. Bennett P, Perini E. Tail docking in dogs: can attitude change be

achieved? Vet J 2003;81:277–282.

3. Root Kustritz MV. Effects of surgical sterilization on canine and feline

health and on society. Reprod Domest Anim 2012;47:214–222.

4. Hart B, Hart L, Thigpen A, et al. Long-term health effects of neutering

dogs: comparison of Labrador Retrievers with Golden

Retrievers. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e102241.

5. Broughton A. Cropping and docking: a discussion of the controversy

and role of law in preventing unnecessary cosmetic

surgery in dogs. Available at: www.animallaw.info/article/

cropping-and-docking-discussion-controversy-and-role-lawpreventing-

unnecessary-cosmetic. Accessed Nov 28, 2014.

6. Noonan GJ, Rand JS, Blackshaw JK, et al. Tail docking in dogs:

a sample of attitudes of veterinarians and dog breeders in

Queensland. Aust Vet J 1996;73:86–88.

7. Weber GH, Morton JM, Keates H. Postoperative pain and perioperative

analgesic administration in dogs: practices, attitudes and

beliefs of Queensland veterinarians. Vet J 2012;90:186–193.

8. Landsberg G, Hunthausen W, Ackerman L. Behavior problems

of the dog & cat. 3rd ed. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2012.

9. Diesel G, Pfeiffer D, Crispin S, et al. Risk factors for tail injuries

in dogs in Great Britain. Vet Rec 2010;166:812–817.

10. Cameron N, Lederer R, Bennett D, et al. The prevalence of tail

injuries in working and non-working breed dogs visiting veterinary

practices in Scotland. Vet Rec 2014;174:450.

11. Lederer R, Bennett D, Parkin T. Survey of tail injuries sustained by

working gun dogs and terriers in Scotland. Vet Rec 2014;174:451.

12. Hytonen MK, Grall A, Hedan B, et al. Ancestral t-box mutation

is present in many, but not all, short-tailed dog breeds. J Hered

2009;100:236–240.

13. Cattanach B. Bobtail Boxers. Available at: bobtailboxers.com/

the-cross-corgi-ex-boxer. Accessed Mar 15, 2015.

14. Noonan GJ, Rand JS, Blackshaw JK, et al. Behavioural observations

of puppies undergoing tail docking. Appl Anim Behav

Sci 1996;49:335–342.

15. Wansbrough R. Cosmetic tail docking of dogs. Aust Vet J

1996;74:59–63.

16. Gross T, Carr S. Amputation neuroma of docked tails in dogs.

Vet Pathol 1990;27:61–62.

17. Eicher SD, Cheng HW, Sorrells AD, et al. Short communication:

behavioral and physiological indicators of sensitivity of chronic

pain following tail docking. J Dairy Sci 2006;89:3047–3051.

18. Jensen T, Nikolajsen L. Phantom pain and other phenomena

after amputation. In: Wall P, Melzack R, eds. Textbook of pain.

4th ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1999;799–814.

19. Leaver S, Reimchen T. Behavioural responses of Canis familiaris

to different tail lengths of a remotely-controlled life-size

dog replica. Behaviour 2008;145:377–390.

20. Henderson R, Horne R. The pinna. In: Slatter D, ed. Small animal

surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier Science,

1993;1545–1559.

21. Rosser E. Causes of otitis externa. Vet Clin North Am Small

Anim Pract 2004;34:459–468.

22. Hayes HM Jr, Pickle LW, Wilson GP. Effects of ear type and

weather on the hospital prevalence of canine otitis externa.

Res Vet Sci 1987;42:294–298.

23. Lehner G, Sauter Louis C, Mueller R. Reproducibility of ear cytology

in dogs with otitis externa. Vet Rec 2010;167:23–26.

24. Fernandez G, Barboza G, Villabos A. Isolation and identification

of microorganisms present in 53 dogs suffering from otitis externa.

Rev Cient 2006;16:23–30.

25. Henderson R, Horne R. The pinna. In: Slatter D, ed. Textbook

of small animal surgery. Vol 1. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders

Elsevier Science, 2003;1737–1746.

26. Crook A. Cosmetic surgery in North America and Latin America,

in Proceedings. World Small Animal Veterinary Association

World Congress 2001; 54–55.

27. Ciucci P, Lucchini V, Boitani L, et al. Dewclaws in wolves

as evidence of admixed ancestry with dogs. Can J Zool

2003;81:2077–2081.

28. Park K, Kang J, Park S, et al. Linkage of the locus for canine

dewclaw to chromosome 16. Genomics 2004;83:216–224.

29. Savant-Harris M. Removal of dew claws. In: Canine reproduc170

JAVMA • Vol 248 • No. 2 • January 15, 2016

tion and whelping: a dog breeder’s guide. Wenatchee, Wash:

Dogwise Publishing, 2005.

30. Becker M. Does our puppy need his dewclaws? Available at:

www.vetstreet.com/dr-marty-becker/does-our-puppy-needhis-

dewclaws. Accessed Nov 28, 2014.

31. Hedlund CS. Surgery of the integumentary system. In: Fossum T,

ed. Small animal surgery. 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby, 2007;254–255.

32. Hedlund CS. Surgery of the integumentary system. In: Fossum T,

ed. Small animal surgery. 4th ed. St Louis: Mosby, 2011;251–259.

33. Robinson DA, Romans CW, Gordon-Evans WJ, et al. Evaluation

of short-term limb function following unilateral carbon dioxide

laser or scalpel onychectomy in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc

2007;230:353–358.

34. Yeon SC, Flanders JA, Scarlett JM, et al. Attitudes of owners regarding

tendonectomy and onychectomy in cats. J Am Vet Med

Assoc 2001;218:43–47.

35. Fatjo J, Ruiz-de-la-Torre J, Manteca X. The epidemiology of behavioural

problems in dogs and cats: a survey of veterinary

practitioners. Anim Welf 2006;15:179–185.

36. de Souza-Dantas L, Soares G, D’Almeida J, et al. Epidemiology of domestic

cat behavioural and welfare issues: a survey of Brazilian referral

animal hospitals in 2009. Int J Appl Res Vet Med 2009;7:130–137.

37. Strickler B, Shull E. An owner survey of toys, activities, and behavior

problems in indoor cats. J Vet Behav 2014;9:207–214.

38. Ramos D, Mills DS. Human directed aggression in Brazilian domestic

cats: owner reported prevalence, contexts and risk factors.

J Feline Med Surg 2009;11:835–841.

39. Cozzi A, Leucelle CL, Monneret P, et al. Induction of scratching

behaviour in cats: efficacy of synthetic feline interdigital

semiochemical. J Feline Med Surg 2013;15:872–878.

40. Patronek GJ, Glickman LT, Beck AM. Risk factors for relinquishment

of cats to an animal shelter. J Am Vet Med Assoc

1996;209:582–588.

41. Heidenberger E. Housing conditions and behavioural problems

of indoor cats as assessed by their owners. Appl Anim

Behav Sci 1997;52:345–364.

42. Patronek GJ. Assessment of claims of short and long term complications

associated with onychectomy in cats. J Am Vet Med

Assoc 2001;219:932–937.

43. Lockhart LE, Motsinger-Reif AA, Simpson WM, et al. Prevalence

of onychectomy in cats presented for veterinary care near Raleigh,

NC and educational attitudes toward the procedure. Vet

Anaesth Analg 2014;41:48–53.

44. Carroll GL, Howe LB, Slater MR, et al. Evaluation of analgesia provided

by postoperative administration of butorphanol to cats undergoing

onychectomy. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998;213:246–250.

45. Cloutier S, Newberry R, Cambridge A, et al. Behavioural signs

of postoperative pain in cats following onychectomy of tenectomy

surgery. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2005;92:325–335.

46. Clark K, Bailey T, Rist P, et al. Comparison of 3 methods of onychectomy.

Can Vet J 2014;55:255–262.

47. Holmberg D, Brisson B. A prospective comparison of postoperative

morbidity associated with the use of scalpel blades and

lasers for onychectomy in cats. Can Vet J 2006;27:162–163.

48. Jankowski AJ, Brown DC, Duval J, et al. Comparison of effects

of elective tenectomy or onychectomy in cats. J Am Vet Med

Assoc 1998;213:370–373.

49. Tobias KS. Feline onychectomy at a teaching institution: a retrospective

study of 163 cases. Vet Surg 1994;23:274–280.

50. Pollari FL, Bonnett BN. Evaluation of postoperative complications

following elective surgeries of dogs and cats in private

practices using computer records. Can Vet J 1996;37:672–678.

51. Landsberg G. Cat owners’ attitudes towards declawing. Anthrozoos

1991;4:192–197.

52. CVMA website. Onychectomy (declaw) of the domestic felid. Available

at: www.canadianveterinarians.net/documents/onychectomyof-

the-domestic-felid. Accessed Nov 28, 2014.

53. Mengoli M, Mariti C, Cozzi A, et al. Scratching behaviour and

its features: a questionnaire-based study in an Italian sample of

domestic cats. J Feline Med Surg 2013;15:886–892.

54. Monnet E. Small animal soft tissue surgery. John Wiley &

Sons, Inc, 2013.

55. New J Jr, Salman M, King M, et al. Characteristics of shelterrelinquished

animals and their owners compared with animals

and their owners in US pet-owning households. J Appl Anim

Welf Sci 2000;3:179–201.

56. Wells DL, Hepper PG. Prevalence of behaviour problems reported

by owners of dogs purchased from an animal rescue

shelter. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2000;69:55–65.

57. Stafford K. Training methods. In: Stafford K, ed. The welfare of

dogs. Dordecht, the Netherlands: Springer, 2007.

58. Yin S, Fernandez E, Pagan S, et al. Efficacy of a remote-controlled,

positive-reinforcement, dog-training system for modifying

problem behaviors exhibited when people arrive at the

door. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2008;113:123–138.

59. Flint E, Minot E, Stevenson M, et al. Barking in home alone suburban

dogs (Canis familiaris) in New Zealand. J Vet Behav 2013;8:302–305.

60. Wells D. The effectiveness of a citronella spray collar in reducing

certain forms of barking in dogs. Appl Anim Behav Sci

2001;73:299–309.

61. Steiss J, Schaffer C, Ahmad H, et al. Evaluation of plasma cortisol

levels and behavior in dogs wearing bark control collars. Appl

Anim Behav Sci 2007;106:96–106.

62. Schilder M, van der Borg J. Training dogs with help of the shock

collar: short and long term behavioural effects. Appl Anim Behav

Sci 2004;85:319–334.

63. Mehl ML, Kyles AE, Pypendop BH, et al. Outcome of laryngeal

web resection with mucosal apposition for treatment of airway

obstruction in dogs: 15 cases (1992–2006). J Am Vet Med

Assoc 2008;233:738–742.

64. CVMA. Cutting canine teeth in adult dogs, and deciduous teeth in

puppies. Available at: www.canadianveterinarians.net/documents/

cutting-canine-teeth-in-dogs-and%20deciduous%20teeth-in-puppies.

Accessed Mar 3, 2014.

65. United States Department of Agriculture. Animal welfare: policy#

3: veterinary care. Available at: www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_

welfare/policy.php?policy=3. Accessed Mar 6, 2014.

66. Council of Europe. European convention for the protection

of pet animals. Available at: conventions.coe.int/Treaty/en/

Treaties/Html/125.htm. Accessed Nov 28, 2014.

67. Lefebvre D, Lips D, Giffroy JM. The European convention for

the protection of pet animals and tail docking in dogs. Rev Sci

Tech 2007;26:619–628.

68. AVMA. Ear cropping and tail docking of dogs. Available at:

www.avma.org/KB/Policies/Pages/Ear-Cropping-and-Tail-

Docking-of-Dogs.aspx. Accessed Dec 15, 2014.

69. CVMA. Cosmetic alterations. Available at: www.canadianveterinarians.

net/documents/cosmetic-alteration. Accessed Nov 28, 2014.

70. American Kennel Club. Canine legislation position statement. Available

at: images.akc.org/pdf/canine_legislation/position_statements/

Ear_Cropping_Tail_Docking_and_Dewclaw_Removal.pdf. Accessed

Nov 28, 2014.

71. AVMA. Welfare implications of canine devocalization. Available

at: https://www.avma.org/KB/Resources/LiteratureReviews/

Documents/Backgrounder-Canine%20Devocalization-Final.

pdf. Accessed Dec 1, 2015.

72. CVMA. Devocalization of dogs. Available at: www.canadianveterinarians.

net/documents/devocalization-of-dogs#.UxT7yvmwKyI.

Accessed Mar 3, 2014.

73. The College of Veterinarians of Ontario. Medically unnecessary

veterinary surgery (“Cosmetic surgery”). Available at: www.cvo.

org/CVO/media/College-of-Veterinarians-of-Ontario/Resources

%20and%20Publications/Position%20Statements%20and%20

Guidelines/MUVSCosmeticSurgery.pdf. Accessed Nov 27, 2014.

74. Newfoundland and Labrador. Animal health and protection act.

Available at: www.assembly.nl.ca/legislation/sr/statutes/a09-1.

htm#76_. Accessed May 15, 2015.

75. AVMA. State law governing elective surgical procedures. Available

at: www.avma.org/Advocacy/StateAndLocal/Pages/srelective-

procedures.aspx. Accessed Nov 27, 2014.

76. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts. An act prohibiting devocalization

of dogs and cats. Available at: malegislature.gov/Laws/

SessionLaws/Acts/2010/Chapter82. Accessed May 15, 2015.

77. Australian Veterinary Association. Surgical alteration to the natural

state of animals. Available at: www.ava.com.au/policy/31-

surgical-alteration-natural-state-animals. Accessed May 15, 2015.

78. Rollin B. Animal production and the new social ethic for animals,

in Proceedings. Food Anim Well-Being Conf Workshop 1993;3–13.

JAVMA • Vol 248 • No. 2 • January 15, 2016 171

79. American Kennel Club. Frequently asked conformation questions.

Available at: www.akc.org/events/conformation/faqs.cfm.

Accessed Feb 25, 2014.

80. Council of Docked Breeds. Available at: www.cdb.org/. Accessed

Mar 6, 2014.

81. Atwood-Harvey D. Death or declaw: dealing with moral ambiguity

in a veterinary hospital. Soc Anim 2005;13:315–342.

82. Croney C. Words matter: implications of semantics and imagery in

framing animal-welfare issues. J Vet Med Educ 2010;37:101–106.

83. Weary D, Niel L, Flower F, et al. Identifying and preventing pain

in animals. Appl Anim Behav Sci 2006;100:64–76.

84. Robertson SA, Lascelles BD. Long-term pain in cats: how much

do we know about this important welfare issue? J Feline Med

Surg 2010;12:188–199.